21/11/2024

Translation-oriented writing for machine translation

Texts are usually written to be read by people. However, as AI is being increasingly used to both create and translate texts, it is also very important that texts can be read by machines. If a text is to be machine-translated, there are a number of aspects that can be taken into account when creating a text to have a positive effect on the machine translation (MT) output. We will show you some potential stumbling blocks when using MT systems and potential solutions to significantly reduce sources of error and the amount of post-editing required for machine translation.

Keeping the machine in mind

Translation-oriented writing involves keeping the future translation process in mind when creating the source-language content. In our article on translation-oriented writing for working with CAT tools, we also discussed the impact that layout and terminology have on translatability and, most importantly, on the reusability of translations in translation memories. Although many of the aspects identified in that article make it difficult to process – and, in some cases, to understand – the text, in the human translation process they can be identified and corrected.

The situation is different when a text is being translated by a machine rather than a human. The DIN 8579 standard “Translation-oriented writing – Text production and evaluation” lists requirements for translation-oriented texts and explicitly assesses their relevance for machine translation. Of the 47 criteria, 40 are rated as relevant for MT and a further three as having limited relevance. Therefore, almost all the requirements for translation-oriented writing in relation to formatting, terminology, style, syntax, clarity and logic apply to MT translation as well as to human translation.

Translation-oriented writing aims to reduce additional costs, loss of time and translation errors. These objectives also apply to machine translation, which is normally used to save time and/or costs. In the case of human translation, an additional aim is to reduce the need for queries. This is where there is a clear difference between the two processes, as machine translation systems do not ask any questions. Every error in the MT system leads to increased costs in post-processing or may represent a risk, if it is not detected. There are potential risks hiding at various points in texts and in the MT process.

Segmentation and context

Machine translation can be used as a standalone solution or can be integrated into third-party applications. In the standalone version, texts or files can be translated on a provider’s web interface. To use MT in text creation systems or translation systems, plug-ins are normally used, for example to enable translation in MS Office apps. In the professional translation sector, it is integrated into CAT tools so that the machine translation can be used as an additional resource alongside the translation memory.

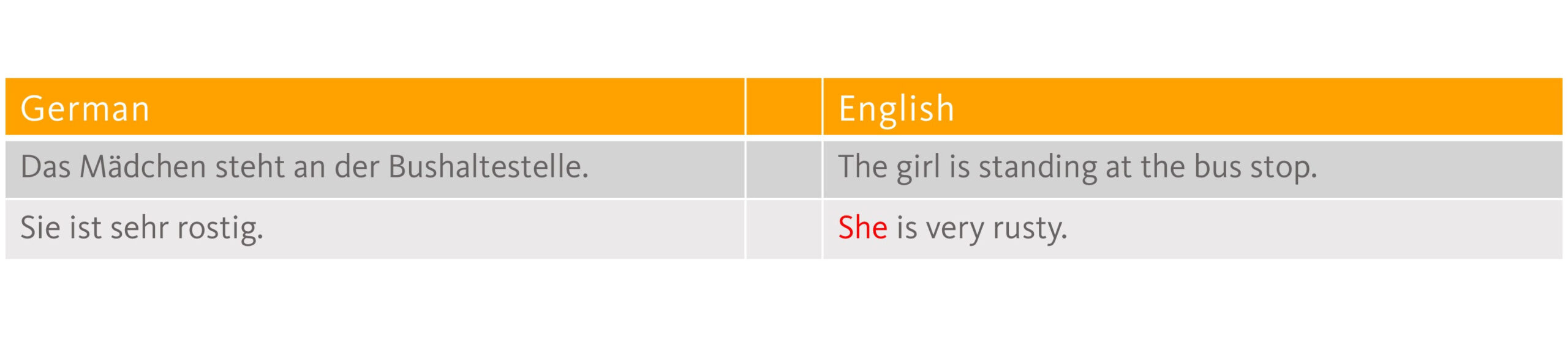

To identify potential for errors, it is helpful to understand the basics of how MT systems work. When MT is used in CAT tools, the text is segmented very clearly, as each text is included and translated segment by segment or sentence by sentence. But even if an entire document is sent to an MT system, segmentation still takes place in the background. In terms of identifying logical connections, this means that MT systems only recognise context up to the end of a sentence or segment. This means that references, such as pronouns, are not identified across sentence boundaries, as the following example shows:

According to the translation, it is not the bus stop that is rusty, but the girl. To avoid this problem, either references must be made clear by repeating the relevant word or logically connected sentences must be linked together to remove the boundary between them:

Large language models have an advantage here, as they look at a text in its overall context and do not break them up into segments.

Breaks and sentence structure

Breaks inserted manually within a sentence are one obvious source of error in MT translations. They are used, for example, to break a line at a certain point in the sentence. MT systems work on the basis of word probabilities. For each word in the sentence, the system calculates the probability of a given word occurring together with this word based on the frequency with which they occurred together in the machine’s training material. While this can indeed produce fluent and coherent translations, it can also produce undesirable results if sentences are broken up manually. This is because the MT system attempts to complete each part of the sentence with the information that appears to be missing, meaning that the original statement may get lost or additional information may appear in the target text. Often, independent clauses are placed next to each other that no longer have any logical link.

Hard, manually inserted breaks should therefore be avoided at all costs. As an alternative, soft line breaks (↵) can be used. They serve the same purpose, but are not treated as stop marks. In a translation, however, breaks may be placed in completely different positions due to different sentence lengths. As a result, they may no longer serve the original purpose of the text break, if it was inserted in a specific place.

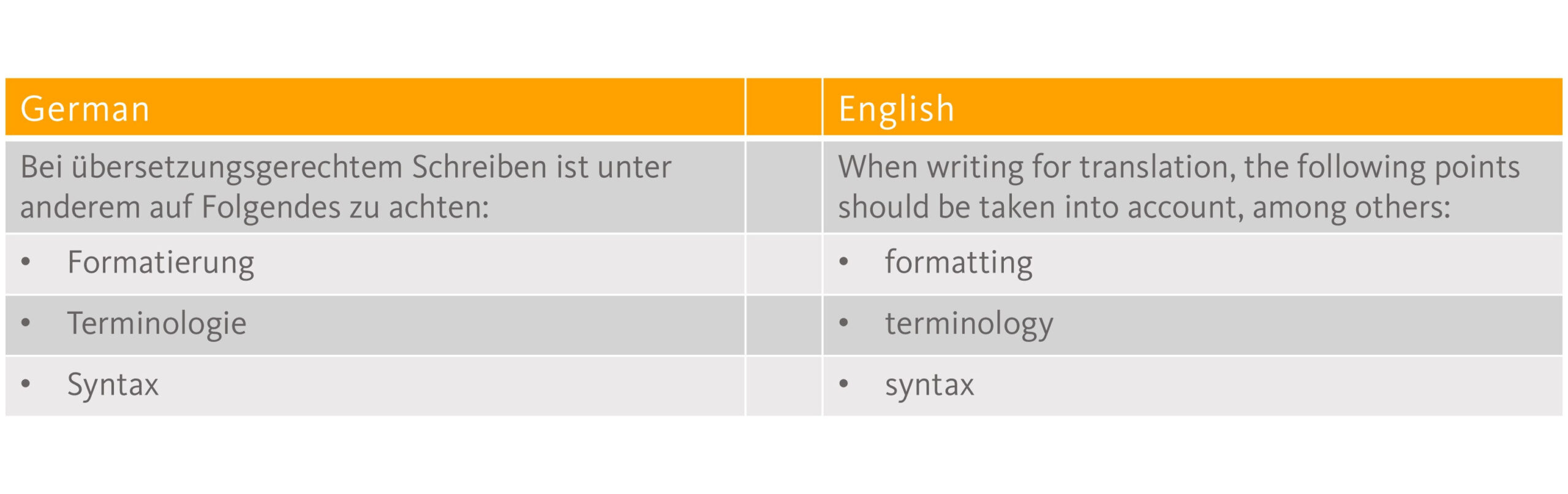

In terms of sentence structure, machine translation also causes problems with sentences in which the verb is very far away from the subject, phrases without a verb, or as is often the case in German, lists that are only completed with a verb that comes at the end. In sentences with ‘sentence brackets’, for example where the two parts of a separable verb are split up, the MT system adds the information that seems to be missing to the first, incomplete part of the sentence. These additions can be very helpful if words have actually been forgotten, but, when there are ‘sentence brackets’, it often leads to duplications and, therefore, incorrect translations:

One solution is to formulate sentences as completely and coherently as possible. In the example shown above, the whole of the introduction to the list can come before the first bullet point, avoiding a sentence bracket:

Formatting

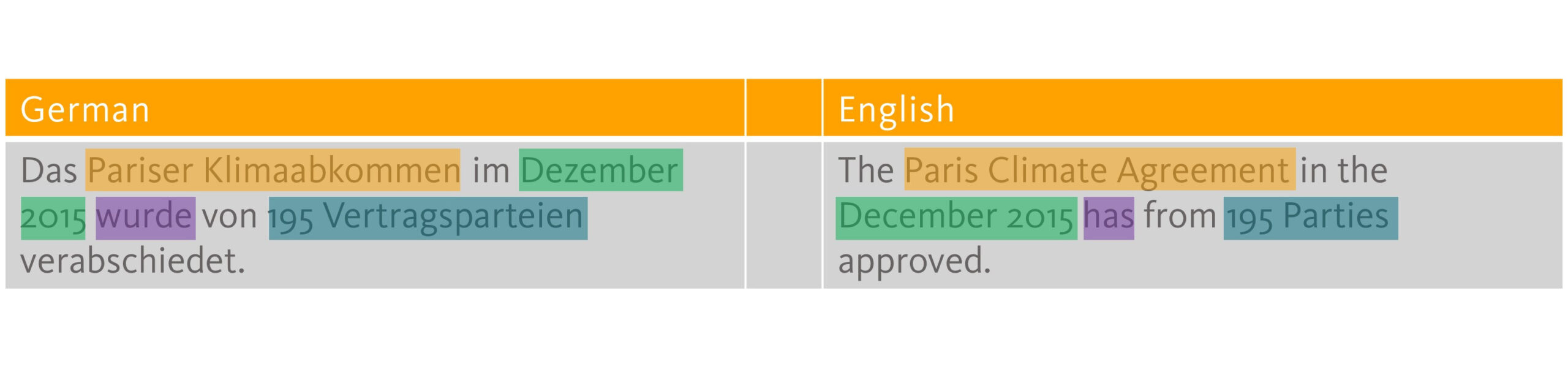

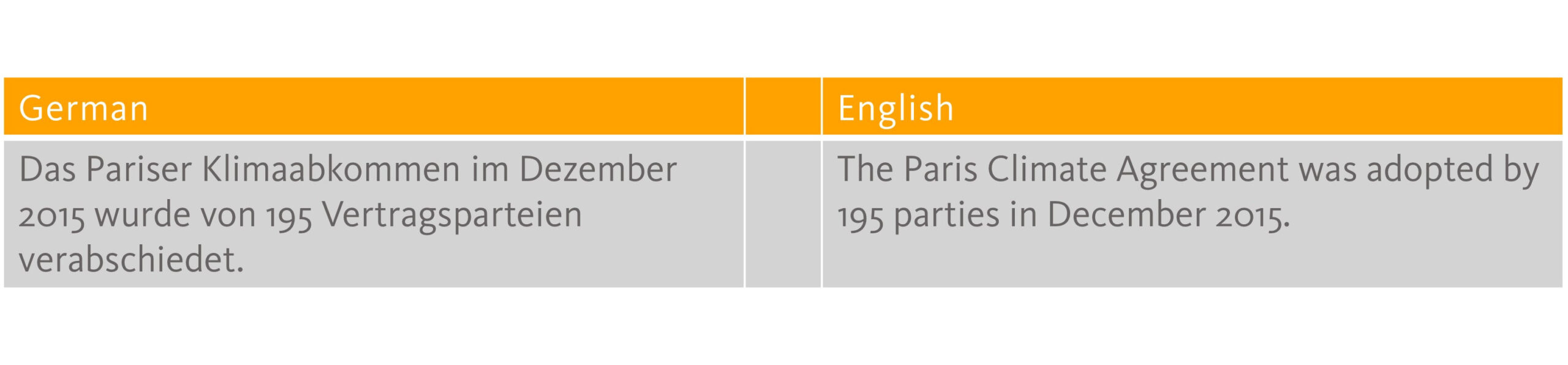

Depending on the MT system, different formatting within a sentence – such as bold, italics or different font colours – can cause translation difficulties. Some MT systems regard each formatted piece of text as a separate part of a sentence. If there is a high density of formatting, this can quickly lead to word-for-word translations:

To minimise this phenomenon, it makes sense to test how the MT system you are using handles a range of formatting types. PowerPoint files are particularly susceptible to mistranslations due to formatting and should therefore be checked separately. If mistranslation occurs in the MT system, the formatting should be limited to what is absolutely necessary and preference should be given to reformatting after translation.

When translating in CAT systems, source text formatting is displayed as tags in the translation editor. When using MT systems, tags are often shifted, omitted or added, with the result that the formatting is not applied correctly to the target text. In some MT systems, all tags in a sentence may be listed at the beginning of the sentence. Even if it has little or no effect on the translation of the text, formatting also causes potential for errors in CAT tools, leading to more editing work afterwards.

Terminology

In both human and machine translation, technical terms are an important factor in ensuring that the text is correct, appropriate and comprehensible. However, depending on the MT system, language combination and subject area of the text, the machine translation may be very far removed from the terminology that a company uses or wants to be used. First of all, MT systems do not natively know the desired terminology. Secondly, each term is translated based on word probabilities. This means that even terms that are used consistently and correctly in the source text can still be translated differently from sentence to sentence in the MT output. As mentioned above, machines do not look at an overall context, but at individual sentences. This means that they do not make connections or create consistency between terms across an entire document. Therefore, as well as terminology errors or inaccuracies, inconsistencies are to be expected in machine output.

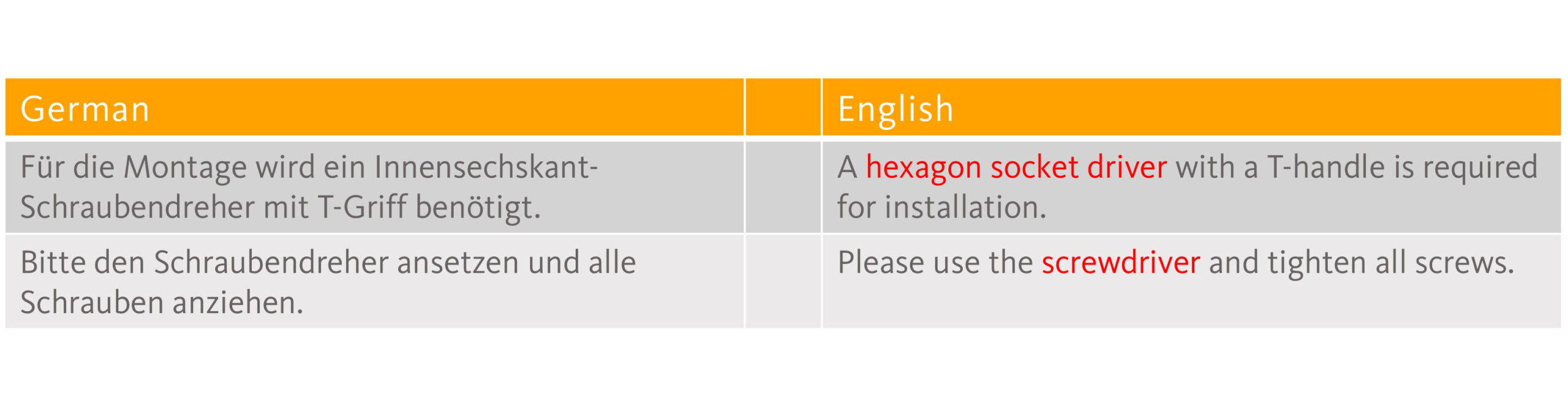

Particular attention should be given to permitted synonyms – for example short forms of words – that are used in the source text to avoid repetition. For example, if a term such as “Innensechskant-Schraubendreher” is shortened to “Schraubendreher” in the next sentence, human translators and readers are likely to be able to connect the two. For MT systems, however, once one sentence ends another one begins, without any connection with the previous text. The system then uses the statistically most probable translation for “Schraubendreher”:

When using MT systems, it is therefore important to avoid short forms of words and to always use the full version of technical terms wherever possible. Even if the machine translates terms inconsistently, consistent terminology in the source text makes it possible to search for a specific term to correct it in the machine output.

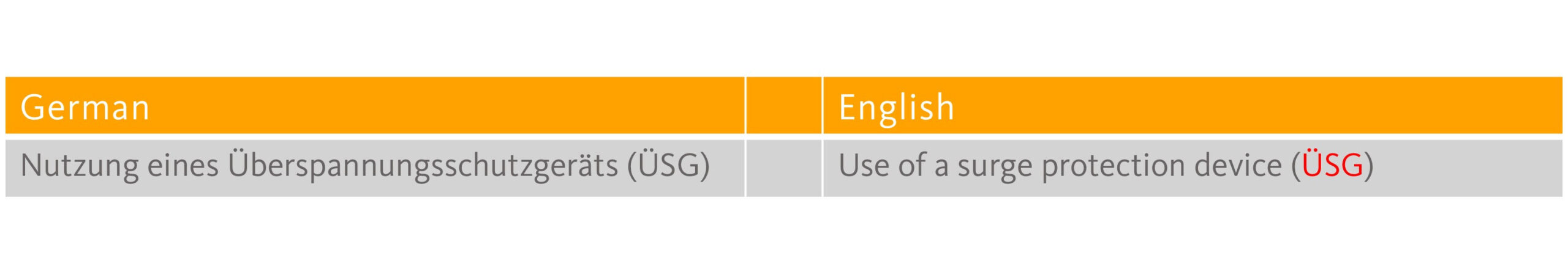

Acronyms are another stumbling block in machine translation. With the exception of very common acronyms such as EU, UN or GDPR, MT systems usually leave acronyms unaltered:

Acronyms should therefore be avoided where possible and, instead, words should be written out in full. A glossary can be integrated into some MT systems as a solution for all the points mentioned – technical terms, short forms and acronyms. Preferred terminology is defined for each language direction, which the system then applies in the machine translation. This can include not only technical terms but also phrases, general language words, and even acronyms and short forms, if they would otherwise cause errors in the machine output.

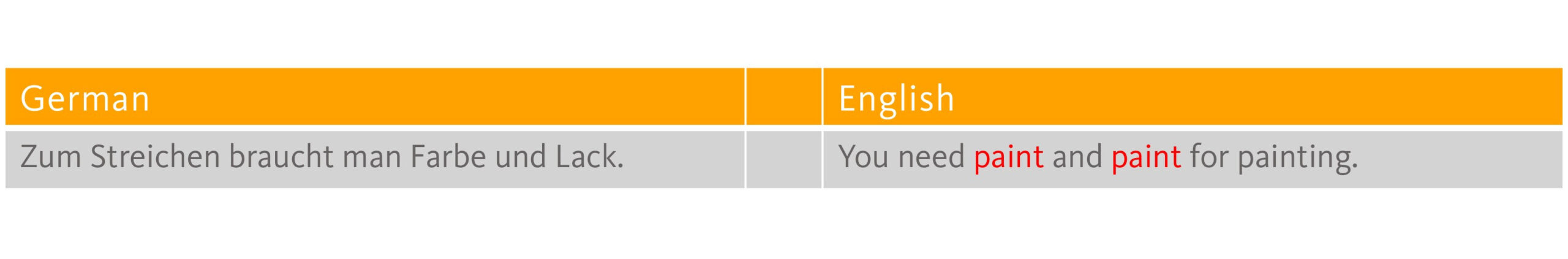

A glossary also makes it possible to differentiate between similar words that would otherwise be translated identically by the MT system. This is because the systems tend to use fairly simple, common words due to the fact that they are calculating word probabilities and training with very large amounts of data. This can lead to different but semantically similar words being translated in the same way:

This can be remedied with a suitable glossary entry, for example “Lack = varnish”, which provides a clear differentiation of terms.

In some special cases, however, MT systems ignore the glossary. This can be due to context sensitivity, meaning that the machine still calculates the statistical probability for each glossary term and does not use the specified term if it is unlikely according to the training material. Some MT systems also ignore punctuation marks within a glossary entry, for example the hyphen in split compound words such as “Luft- und Kriechstrecken”. There is then no link between the separated part of the word and the base word. This means that the separated part is translated as a standalone word. Split compound words should therefore be written out in full before the machine translation process, in this case as “Luftstrecken und Kriechstrecken”, to create clarity for the MT.

Multilingualism, references and the meta level

Even though MT systems seem to be able to switch effortlessly between different languages and many online services offer an option for automatic language recognition, the presence of more than one language in the source text is a potential source of error in machine translation. For example, if a German text is being translated into English and already contains some English in lists or bilingual tables, the English parts of the text are often “translated” and end up being worded differently.

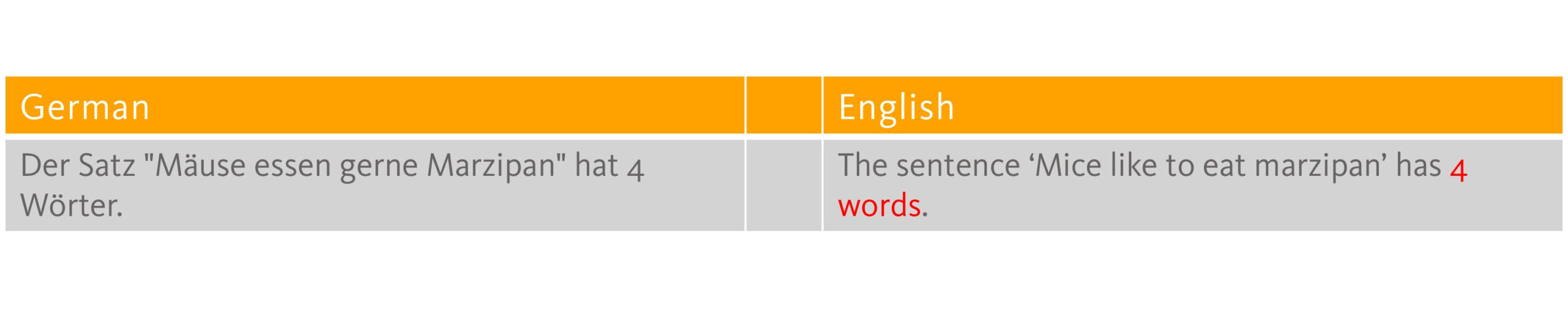

MT systems cannot handle culture-specific references, such as units of measurement, the names of institutions, idioms or example sentences for particular phenomena. They also cannot make changes at a meta level, for example statements about sentence length or the number of words contained in a text:

Just as the MT system in the example shown here cannot count the words in an English sentence, it also cannot search for references to other documents, legal texts or standards. Explicit references to these types of secondary texts can only be translated by the MT system and therefore may not match the actual title of the foreign-language text. In addition to the multilingualism mentioned above, machine translation also does not consider whether certain words or phrases need to be retained in the source language and not translated.

Any cultural specifics and references to reference documents must therefore be translated before the machine translation or corrected afterwards. Each document should also be checked for the presence of multiple source languages. Any content already in the target language does not have to be processed by the MT system. This avoids the risk of this content being “translated”, potentially producing unwanted changes to the content.

Conclusion: Preparation instead of rework

Even though machine translation has been used in everyday business for some time, there are a few points to bear in mind when preparing a text to avoid things that machines can “stumble” over. Segmentation, sentence structure, formatting and terminology are just some of the aspects that play a role in translation-oriented writing for machine translation. As a general principle, the wording should be as explicit and complete as possible, as references across sentences, synonymous technical terms and the use of short forms can all lead to errors.

It is worth putting some effort into preparing the text – a process known as pre-editing – to eliminate potential sources of error when using MT, especially if there are many target languages and large volumes of text.

If the source text is easy for machines to read, then hopefully the target text will be too for the readers.

Would you like to learn more about translation-oriented writing for machine translation? Then contact us today for a personalised consultation.

8 good reasons to choose oneword.

Learn more about what we do and what sets us apart from traditional translation agencies.

We explain 8 good reasons and more to choose oneword for a successful partnership.